Taekwondo 태권도Taekwondo Preschool

Korean martial arts are military practices and methods which have their place in the history of Korea but have been adapted for use by both military and non-military personnel as a method of personal growth or recreation.

About Korean Martial Arts 무술

Korean martial arts are military practices and methods which have their place in the history of Korea but have been adapted for use by both military and non-military personnel as a method of personal growth or recreation.

Korean martial arts (Hangul: 무술 or 무예, Hanja: 武術 or 武藝) are military practices and methods which have their place in the history of Korea but have been adapted for use by both military and non-military personnel as a method of personal growth or recreation. Among the best recognized Korean practices using weapons are traditional Korean Archery and Kumdo, the Korean sword sport similar to Japanese Kendo. The best known unarmed Korean Martial Arts Taekwondo and Hapkido though such traditional practices such as ssireum - Korean Wrestling - and taekkyeon - Korean Foot Fighting - are rapidly gaining in popularity both inside and outside of the country.

In November 2011, Taekkyeon was recognized by UNESCO and placed on its Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity List. There has also been a revival of traditional Korean swordsmanship arts as well as knife fighting and archery. Today, Korean martial arts are being practiced worldwide. More than one in a hundred of the world's population practices some form of taekwondo.

Early History

Wrestling, called ssireum, is the oldest form of ground fighting in Korea. While, subak/taekkyeon was the foot soldiers upright martial art. Weapons being an extension of those unarmed skills. Both tradition martial arts, besides being used to train soldiers, were also popular among villagers during festivals for dance, mask, acrobatics, and sport fighting. These martial arts were also basic physical education. Koreans, as with the neighbouring Mongols, relied more heavily on bows and arrows in warfare than they did on close-range weapons.

It appears that during the Goguryeo dynasty, (37 BC – 668) subak/taekkeyon or ssireum (empty-handed fighting), swordsmanship, spear-fighting and horse riding were practiced. Paintings showing martial arts were found in 1935 on the walls of royal tombs, believed to been built for Goguryeo kings, sometime between 3 and 427. Which techniques were practiced during that period is however something that cannot be determined from these paintings. References to subak can be found in government records from the Goguryeo dynasty through the Joseon dynasty (1392-1910).

It is believed that the warriors from the Silla Dynasty (57 BC-668 AD) learned subak from the neighboring Goguryeo armies when they appealed for their help against invading Japanese pirates. Practicing subak became part of the training for Silla's hwarang, and this contributed to the spread of subak on the Korean peninsula.

The Buddhist influence on the hwarang is most notably seen around 600 AD when the moral code Sae Sok O-Gye (세속오계), written by Won Kwang (원광, 圓光), consisting of five rules were documented:

Loyalty to one's king 사군이충

Respect to one's parents 사친이효

Faithfulness to one's friends 교우이신

Courage in battle 임전무퇴

Justice in killing 살생유택

The development of Subak continued during the Goryeo Dynasty (935–1392). Goryeo records that mention the martial arts always include passages about SUBAK. The Joseon government, however, outlawed the practice of SUBAK as a public spectacle in response to the large numbers of Korean farmers and landowners whose betting practices included wagering land and sometimes family members. As a concession to public pressure, the government allowed a lesser practice - Taekkyeon games - be used as a form of civilian recreation.

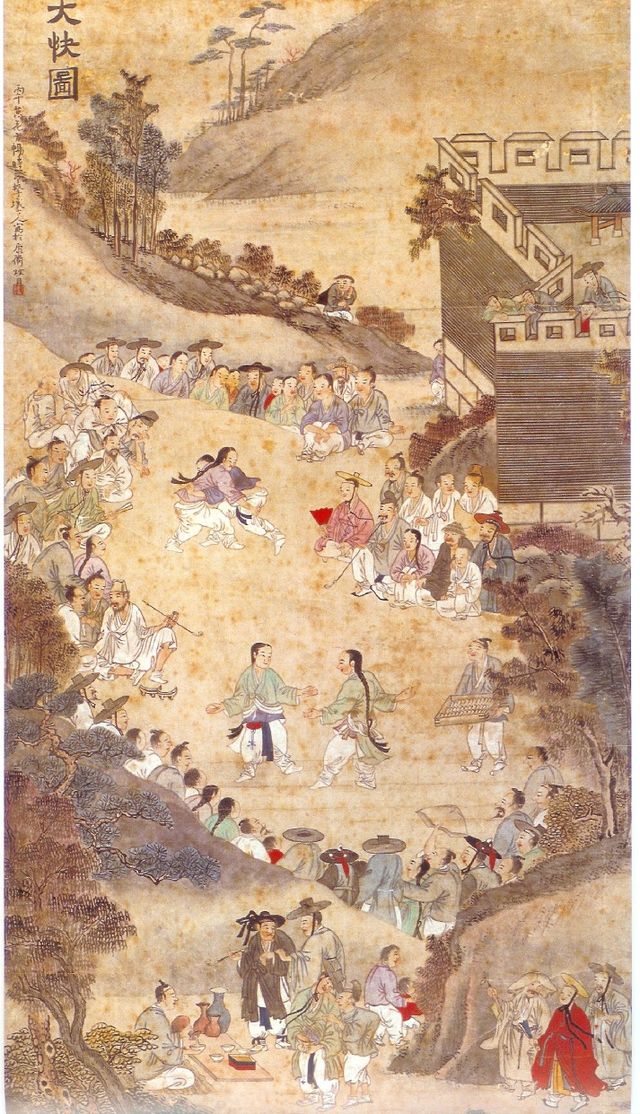

Joseon Dynasty records and books often mention taekkyeon, and taekkyeon players are portrayed on several paintings from that era. The most famous painting is probably the Daegwaedo (Hangul: 대괘도, Hanja: 大快圖), painted in 1846 by Hyesan Yu Suk (혜산 유숙, 1827–1873), which shows men competing in both ssireum (씨름) and taekgyeon.

Goryo Period

With Mongol conquest, Korean Military was reorganized around the mounted archer. Armor and weaponry became very similar to the Mongol armor and weaponry. Acrobatic horsemanship (masangjae), Falconry and Polo (Gyeokgu) was imported. Korean Composite bow, which is very similar to the medieval Mongol bow was adopted at this time. The unique construction of the Korean Gakgung bow shows the original form of the Mongol bow, before the Manchus improved it with stronger and bigger ears. As the military class in late Goryeo were almost entirely Mongol in practice, the Joseon Army also carried on the mounted archer tradition. (Yi Seong-gye the founder of Joseon dynasty was a hereditary Mongol darughachi of Korean origin, administering the Mongol Province of Ssangseong in NE Korea. Choi Young had made his reputation fighting for the Mongols in northern china, putting down Han rebellions in the last days of Yuan dynasty.)

Until the publication of Muyedobotongji in 1795, Archery remained the singular Korean Martial Arts, testable during the military portion of the Gwageo or National Service Examination.

Joseon Dynasty Martial Arts

As the continuation of Goryo military, the Joseon military maintained the primacy of the bow as its main stay weapon. Gungdo remained the most prestigious of all martial arts in Korea. Gungdo was the single most important testable event in gwageo, the national service exam used to select Army officers from 1392 to Gabo Reform in 1894 when gwageo system was terminated.

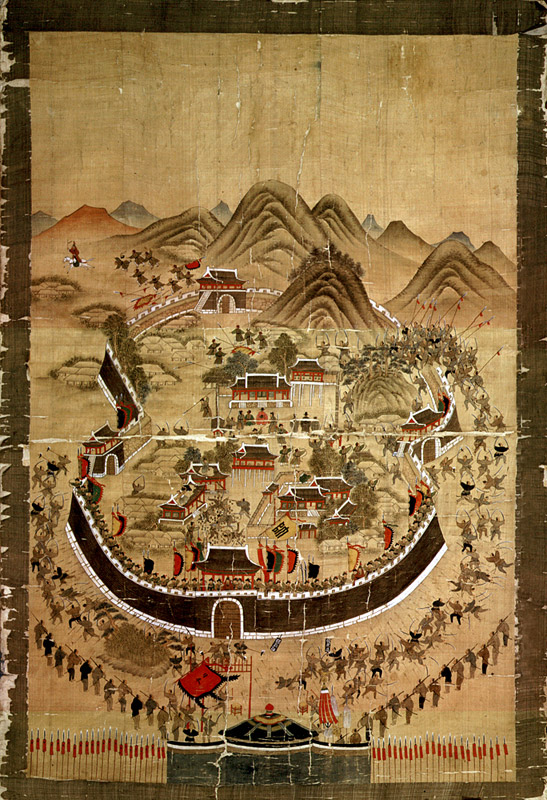

During the Imjin War (1592–1598), Toyotomi Hideyoshi launched the conquest of China's Ming Dynasty by way of Korea. However, after two unsuccessful campaigns towards the allied forces of Korea and China and his death, his forces returned to Japan in 1598. but with heavy loss of men and cultural heritage. It was also during this war that the famous turtle ships (Geobukseon, 거북선) were used by Admiral Yi Sun-sin. These ships were covered with metal shields, much like the shell of a turtle, which could withstand the gun attacks of the Japanese.

In 1593, Korea received help from China to win back Pyongyang. During one of the battles, the Koreans learned about a martial art manual titled Ji Xiao Xin Shu (紀效新書), written by the Chinese military strategist Qi Jiguang. King Seonjo (1567–1608) took a personal interest in the book, and ordered his court to study the book. This led to the creation of the Muyejebo (무예제보, Hanja: 武藝諸譜) in 1599 by Han Gyo, who had studied the use of several weapons with the Chinese army. Soon this book was revised in the Muyejebo Seokjib and in 1759, the book was revised and published at the Muyesinbo (Hangul: 무예신보, Hanja: 武藝新譜).

During the Imjin war, three main weapons were identified by all sides as representative of their armies. The Japanese were known for their arquebus. The Ming Dynasty Chinese forces were known for their lance. Koreans were known for their Pyeonjeon used in conjunction with the Korean composite bow. During the war itself, Korea began adopting the Arquebus, eventually mastering it. Korean arquebusiers became so well known for their ability to kill tigers, which were rampant in Korea throughout its history until its final extermination in 1919, that Ming China requested the assistance of Korean arquebusiers against the rising Manchus in 1619. At the Battle of Sarhu, Korean order of battle was composed of 10,000 arquebusiers out of 13,000 total men. This event illustrates how Korea quickly adopted modern weaponry and discarded close quarter martial arts.

Following the 1636 Second Manchu invasion of Korea, where Manchu composite archers defeated Koreans, who were also mostly composed of archers, supplemented by arquebusiers, the Manchu Qing Dynasty demanded Korean arquebusiers in their battles against Russia in late 1600s. In 1654 and 1658, Joseon deployed 400 of its best tiger hunters as Arquebusiers to fight the Russians along the Amur River during the Sino-Russian border conflicts. Again, no record of swordmen, empty hand martial arts being used or favored by the Korean Army during this period.

In 1790, the Royal Korean Army published the richly illustrated Muyedobotongji (Hangul: 무예도보통지, Hanja: 武藝圖譜通志). The book does not mention ssireum, subak, or taekkyeon, but shows influences from Chinese and Japanese fighting systems. The book, deals mostly with armed combat like sword fighting, double-sword fighting, spear fighting, stick fighting, and so on. The chapter that deals with a style of empty-handed fighting called kwonbeop ("fist methods," a generic name for empty-handed combat; the word is the Korean pronunciation of quanfa) shows techniques that resemble Chinese martial arts—quite different from taekkyeon. According to the Muyedobotongji, empty-handed combat should be learned before armed combat, since it forms the basis of a martial education. It also states that internal styles are better suited for fighting than external styles. The name for the martial arts of the Muyedobotongji is shippalgi. This manual was intended as a training manual for Soldiers in 1790s, as military arts had withered by that time. Despite the publication of this manual, it was never widely distributed, and there was no renaissance of martial arts in Korea.

In 1899, Emperor Gojong of Korean Empire, with the encouragement of Prince Heinrich of Prussia, who was visiting Korea at the time, established Gungdo as an official sport, allowing it to flourish throughout the next century, being recognized by the Japanese Occupation government as a folk art in 1920. The Korean Gungdo Federation was established in Seoul in 1920. Along with Ssireum, Gungdo achieved nation-wide popularity within Korea throughout 1930s and 1940s, even as Japanese martial arts also garnered a large following on the peninsula.

During the Donghak Rebellion, much of the rebels used old matchlock arquebuses against the modern rifles of the Japanese Army. With the annexation of Korea in 1910, all matchlocks were confiscated and destroyed by the Japanese. However, the Japanese did not stop the practice of archery, which they did not consider as a threat to internal security.

Modern Korean Martial Arts

The two extant martial arts at the time of Japanese take over in 1910, Ssireum and Gungdo grew in popularity during the Japanese occupation period, both of them founding their current federations in 1920. Many of the oldest Gungdo clubs in Seoul, including Hwanghakjeong (near Gyeongbokgung Palace) and Sukhojeon on Namsan (Seoul) were founded in 1930s. Taekkyeon did not enjoy much popularity during the occupation era. It has grown in popularity only in the 21st century, after it was revived in 1983 under the military regime.

Most Koreans learned Japanese martial arts during the occupation period, which eventually evolved into Korean martial arts. These include Tae Kwon Do, Hapkido, Soo Bahk Do, Tang Soo Do, Moo Duk Kwan, Kuk Sool Won and Kumdo. The main indicator of their Japanese origin is in their uniform, ranking system, and rules. Traditional Korean clothing (Hanbok) has no belt. Belts used in judo and karate, to include the color code and Geup (Kyu) / Dan (rank) system were adopted wholesale by the Koreans. Rules, to include bowing to the flag, and to the master are direct copies from Japanese martial arts and not found in Ssireum and Gungdo, which flourished in Korea before and during the occupation.

Currently these new arts such as Tae Kwon Do and Hapkido created since 1945 remain the most popular in Korea, with most practitioners being children. Tae Soo Do and Hwa Rang Do, which have a sizeable presence in the US are almost unknown in Korea, as the founders relocated to the US and focused on operations in the US. Gungdo participation is limited by the high cost of the equipment, with a traditional horn made reflex bow costing upwards of $1000, and most Gungdo clubs in Seoul charging over $1000 application fee for membership, similar to golf clubs. This limits participation to the upper and upper middle class. Many Korean junior high schools, high schools, and colleges maintain martial arts teams to include ssireum, kumdo (kendo), judo and Tae Kwon Do. Yong In University south of Seoul focuses on martial arts training for international competitions.

It should also be considered that Korean martial arts are still in a state of evolution as witnessed by recently emerging arts such as Teuk Gong Moo Sool and Yongmoodo. There is now also the development of Korean arts influenced by Western boxing, Muay Thai or Judo, these would include Gongkwon Yusul and Kyuk Too Ki.

Teaching Methods

The traditional Taekkeyon system has no fixed curriculum. Every student is treated individually and thus the lesson is always different, although all of the basic skills are eventually covered. The basic skills are taught in temporary patterns, that evolve as the student learns. Basic skills are expounded on and variations of each single skill are then practised, in multiple new combinations. When the student has learned all the variations of the basic movements & techniques, and can intermix all of them proficiently, they're encouraged to perform the Taekkyeon Dance. Taekkyeon is a Ten-year technique.

Modern Korean martial arts' systemization and presentation are very similar to their Japanese counterparts (i.e., barefoot, with uniforms, classes executing techniques simultaneously by following the teacher's commands, and sometimes, showing respect by bowing to a portrait of the founder and/or to national flags). Many modern Korean martial arts also make use of colored belts to denote rank, tests to increase in rank, and the use of Korean titles when denoting the teacher.

Terminology

Korean martial arts are usually practiced in a dojang (도장), which may also be referred to as cheyukkwan (체육관 / gymnasium). The practitioners wear a uniform or dobok (도복) with a belt or tti (띠) wrapped around it. This belt usually shows which grade the practitioner has attained. A student usually starts with a white belt and moves through a range of colored belts (which differ from style to style) before reaching the black belt. The grades before black belt are referred to as geup or kup (급), while the grades of black belts are referred to as dan (단). In some cases, students less than 16 years old are not given dan grades, but rather "pum" or poom (품) or "junior black belt" grades. Some styles use stripes on the black belt to show which dan the practitioner holds. It is common for a system to have nine geup grades and nine dan grades. While it might only take a few months to go from one geup to the next, it can take years to go from one dan to the next. Most of the above terms are identical to those used in Japanese styles such as judo and karate, but with the Chinese characters read in Korean pronunciation, with a few exceptions (dobok and tti have been altered to fit the Korean language).

In some styles, like taekkyeon, the hanbok is worn instead of a dobok. The v-neck of many styles of taekwondo uniform was supposedly fashioned after the hanbok, but may simply be a modification for a pullover top to accommodate the modesty of female practitioners (standard jacket construction often requires females to wear a T-shirt, leotard, or sport bra underneath the jacket, whereas the pullover v-neck jacket does not).

RESOURCES

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article "Korean Martial Arts", which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike License 3.0.